IT was the mid-1960s, I was in my late teens, I was already becoming familiar with post-war avant-garde music, yet the first time I heard Pli selon Pli by Pierre Boulez, who has died at the age of 90, I couldn’t make head or tail of it. Something in the back of my head, however, insisted that the problem was mine, not the music’s, driving me back to hear it a second time when he conducted it in London again a few months later. This time I was rewarded by a musical experience as scintillating, diaphanous and transcendent as I’ve ever had. When I talked to him about his music a year or two later, I immediately connected the experience with his description of music as ‘controlled hysteria’, an effect which is highly calculated but produces in the listener a peculiar kind of euphoria, a free-floating intensity that can also be found in certain old time composers like Perotin or Tallis, even Beethoven, at least in the readings of certain symphonies by certain conductors–try listening to Boulez’s recording of Beethoven’s Fifth.

I liken my encounter with Pli selon Pli to the first time I saw the films of Glauber Rocha, two of them on the trot at a press show in London in the early 70s, Black God, White Devil and Antonio das Mortes. Again, I couldn’t make them out at all, but I left the viewing theatre with the feeling that the world of cinema had changed, a new dimension had been added–and again this new beauty would be revealed by subsequent viewing.

There are not so many creators in any art form with the power to produce this effect, in which aesthetic order is first destroyed and then restored, disruption leading to a dialectic of reintegration and restitution. Perhaps it is only possible at certain moments in history, notably as a form of aesthetic experience especially linked to the attack of high modernism on the existing perceptual order of bourgeois society, which almost defines the modernist endeavour of figures like Schoenberg, Kandinsky, Joyce, Picasso, Buñuel etc. There are political undertones here, whether or not such artists acknowledged them, which were captured by André Breton, Diego Rivera and Leon Trotsky in their Manifesto: Towards a Free Revolutionary Art of 1938, which declared that ‘True art is unable not to be revolutionary, not to aspire to a complete and radical reconstruction of society.’ Boulez, arriving on the scene in the fluid moment after the war when all traditional cultural forms–bar cinema–were threatened with irrelevance, is rightly to be thought of in this perspective as a late modernist, intent on creating a new sonic world with the power of transforming the established order of perception; nor did he ever dilute his approach. In this respect he contrasts with his fellow post-war enfant terrible, Karlheinz Stockhausen, who after the shock of 1968 evolved a postmodernist ecclectism, with a tendency towards musical megalomania to boot. The first time I interviewed Boulez I asked him what he thought of Stockhausen saying he’d like to write a work that lasted for eternity. He laughed and replied, ‘Oh, but that’s an old German dream’. (Still, Boulez conducted Wagner better than anyone else.)

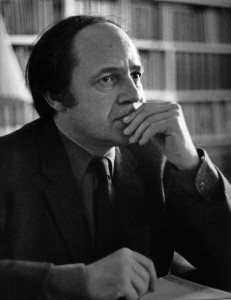

Boulez acquired a reputation in our young circles as a radical not just in musical terms but also–an important question for us–for the critique of bourgeois culture (but I didn’t then know that Adorno had been mentor to Boulez in the Darmstadt days). Around the same time as first hearing Pli selon Pli, a friend started a small magazine (‘Circuit’) and we decided to ask for an interview with him. (Find it here.) He proved a most congenial interviewee who engaged with our earnest questions without the slightest condescension, and I had the feeling he would be open to further encounters. By the time he took up the post of the BBC Symphony Orchestra’s chief conductor, I was earning a modest living as a music critic, which led to a commission to make my first professional film for a music magazine programme on BBC2. I was going to Boulez’s rehearsals and sometimes went with him when he had a free evening to see a film or a play (never music). Everything that obituary writers have been saying about his great courtesy, warm personality, sense of humour and absence of egocentricity is absolutely true (plus the fact that he guarded his private life very closely). There was also for me another aspect–the intellectual education that went with this slightly strange friendship (which had we been speaking French would of course have been conducted in the formal ‘vous’) between the most powerful orchestral conductor in the world, simultaneously at the head of both the BBC Symphony in London and the New York Philharmonic, and a novice documentarist. It was from Boulez that I learned to understand how the institutional order of culture works, with all its contradictions, and I believed him when he said to me that his ascent, once the doors of the establishment had opened, wasn’t something he planned but a matter of following his nose. Boulez was propelled by his genius on the conductor’s podium to the centre of the international musical power structure without, it seemed to me from our conversations, betraying his left wing politics, which he never hid. (It caught up with him once, in the most laughable circumstances. According to a report that turned up on social media a day or two after his death, he was briefly detained by Swiss police in 2001, aged 75, three months after 9/11, when they heard that he had once advocated blowing up opera houses.)

At any rate, the result was the second film I made for the BBC, in 1972, about why he wanted to take the orchestra out of the conventional concert hall to find a more informal venue for avant-garde music and establish a new relationship with the audience. His chosen alternative was the Roundhouse in Chalk Farm, with its strong profile in the radical youth culture of the day. I knew it well as a rock venue, and the venue of the Dialectics of Liberation congress of 1967, convened by R.D.Laing and his associates of the anti-psychiatry movement, which a group of us from Circuit attended together. Since this was where we now found ourselves filming a couple of scenes, the title we adopted, to which Boulez happily agreed, was entirely appropriate: The Politics of Music. It always makes me smile to remember the day he came to the cutting room to watch the rough cut. He picked up a can of film on which typically the laboratory had written the title incorrectly. ‘The Music of Politics’, he read, adding with a twinkle in his eye, ‘Ah, this will be title of my next piece!’

The film almost didn’t happen. With my brother Noel as producer, it was commissioned by a BBC2 arts magazine in unusual circumstances–this was long before the BBC adopted the policy of ‘Producer Choice’, whereby a significant proportion of programmes were made by independent producers on the Channel Four model. Just as the contract was ready to sign, someone realised that it would involve an independent film crew shooting on BBC premises and that this raised a union issue. The sticking point, I seem to remember, was whether the BBC’s house union would allow us to work with an ACTT electrician, or something like that. It was the BBCSO’s genial manager who resolved the problem, because, he told us, he wanted to see the film made. For me, it was a very educational episode, and a few years later the subject I took up for my first scholarly monograph was the history of trades unionism in the film industry.

Another episode that sticks in mind occurred when we went to screen the fine cut, which again Boulez was happy with, to the folk at the BBC. The only substantive comment I recall was the suggestion that it could do with a more traditional piece of music at the start, so as not to frighten viewers off. Boulez was accompanied to the screening by his recording manager, who took me by the arm as we left the viewing theatre and handed me a tape from his briefcase. ‘It’s a piece of Ravel we recorded yesterday, why don’t you use this–you don’t have to tell anyone where you got it.’

The film as broadcast was not quite as we delivered it. The programme editor decided to lift out the sequence of Roger Woodward at home practising and run it as a trailer the week before, so the version transmitted was shorter; in cutting it down, they also lost the end of a long take I was particularly proud of, which is seen here at full length.

[vimeo]http://www.vimeo.com/13799532[/vimeo]

Boulez was in many ways an ideal subject for a first attempt at what was already an established documentary subgenre, the artist portrait, where you follow your subject over a segment of their professional life and interview them. He was never fazed in the slightest by the presence of the camera, on the contrary, he acknowledged it, held the door open for it, even spoke to it. The moment at the beginning of the film when he gets into the car, drops the scores in his arm (into the lap of the unseen sound-recordist lying on the floor), and bending to pick them up remarks, ‘Whoops, that was absolutely live, you know’, this was a gift–a completely unforced moment of documentary self-reflexivity.

The film is built around his incisive and Adornoesque analysis of the history of the figure of the conductor and the social function of the symphony orchestra. I saw his own occupancy of the position in practice in numerous rehearsals. Watching him at work on his own Eclat/Multiples, struggling to read the extremely complex score open on my knees, was revelatory. His method was to prepare sections separately and then to put them together, at first below tempo. Then, when he saw that they fit together, he would play through at speed. I remarked to him that this was particularly instructive for the listener; it revealed the structure, and then produced the exciting sense of suddenly realising the depth of the texture when, listening to the whole construction, you lost hold of the individual lines you’d been following previously: what happened now was that different parts of the texture advanced and receded, the whole thing becoming a pulsating, living organism. Boulez’s response was a wholehearted agreement that this is what should happen, and when he himself felt it happening he knew that the music was working.

He also had immense patience with the players who were sometimes struggling with the unfamiliar idiom, especially an elderly fellow at the celesta who was trying to make his tinkles as ‘expressive’ as he could. Quite the opposite of what he wanted, Boulez courteously asked him to repeat the phrase several times over to expunge all trace of expression and simply let the notes sound. I doubt that any other conductor would have got away with this, but the musicians were in awe of his extraordinarily accurate ear. (He could spot a single wrong note in an orchestral tutti at a hundred yards.) Indeed on one occasion–the dress rehearsal of Pelléas et Mélisande at Covent Garden–he began by tuning the orchestra up section by section, even after they’d tuned themselves. I have seen orchestras behave badly towards one conductor or another. Boulez commanded absolute respect, without ever raising his voice, though he would sometimes throw an offender a withering glance.

The sparkling clarity of his performances made new sense of music familiar as well as unfamiliar. For my part, I had no great love of Bartok’s popular Concerto for Orchestra until I heard Boulez perform it. On one occasion, he stood in for Klemperer who had fallen ill (and whom he greatly admired) in a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth, which was not in Boulez’s normal repetoire. I do believe that the Philharmonia could have given a Klemperer performance of it without anyone on the podium. How did Boulez deal with the problem? He chose faster tempi, resulting in a slightly scrappy but tremendously exciting rendition.

He was completely aware of the difference between rehearsal and performance. I particularly remember when he first turned to Mahler, and I followed the trail through a couple of rehearsals and the performance (I think it was the Sixth Symphony). In rehearsal he keep a tight rein, but he and the orchestra knew that on the night they could let rip, as they did, to give the most stupendous performance of it I had ever heard. I told him it would be wonderful to hear him do Mahler’s First, but he said he couldn’t, it had been completely ruined for him once when he was visiting the music department at Harvard in the early 60s, and one night he was disturbed by a record player blaring out of an open window nearby: it was the first side of Mahler’s First, over and over again.

He had his musical blindspots, of course. The most difficult to forgive was Mozart (but he once did a Mozart piano concerto with, if memory serves, Alicia de Larrocha, and made a perfectly elegant job of it). And I was once the recipient of one of those disapproving looks when I said something about Weill. Adorno had begrudingly acknowledged Weill’s genius in reviewing Die Dreigoschenoper, but Boulez had even less interest than Adorno in commercial music of any kind. He would not have recorded those pieces by Zappa if he hadn’t thought they were musically interesting. But the composers whose entire oeuvre he would never conduct was not simply a matter of personal taste. Those who were anathema invariably wrote the kind of music that Adorno called ideological–they failed to challenge the social order: past composers like Tchaikovsky or Sibelius or Richard Strauss, or those of his contemporaries who continued to write in a harmonic language. He considered Britten to be vulgar: the War Requiem was like ‘incidental music for a film by Cecil de Mille’. You can see the logic, even if you don’t agree.

He had a special distaste for Shostakovich, whom he saw as a Soviet ideologue: ‘Tchaikovsky rewritten in the idiom of Socialist Russia’. He is said by his obituarists to have mellowed in later life, and someone on the radio said that he later described his youthful hostility to the Russian as silly, but the thing is this: his judgement was both musical and political. He thought Shostakovich’s music was full of clichés, but that also meant it was compliant, and this says something about his own political position, both anti-authoritarian and anti-populist at the same time. He was aware of the contradictions this entailed. As he puts it in The Politics of Music, speaking of his role as a conductor, ‘You are confronted with this dilemma: you want to expand liberalism, and you have to force this situation to happen. So at the same time, you have to be a kind of dictator to bring people to more freedom.’

His legacy as a composer is something else again, the very embodiment of the freedom of spirit that is music’s special gift. It was a great privilege to make a film with him, and have got to know him as well as I did.