For left film culture in Britain, Stanley Forman, who has died at the age of 91, was the archive man. His company, ETV, held a unique library of left-wing documentaries which amounted to the history of the twentieth century from a socialist perspective. Established in 1950 as Plato Films, the outfit was what would be called in Cold War ideology a front organisation, set up by members of the Communist Party to distribute films from behind the Iron Curtain. There was nothing nefarious about it, however. It was then the standard practice of the Party in the UK to conduct its cultural work through private companies, like the publisher Lawrence & Wishart and Collett’s the bookshop. Under the slogan ‘See the other half of the world’, Plato provided the movement with a film distributor for documentaries from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, taking in China (until the Sino-Soviet split), Cuba, Vietnam and elsewhere, which would otherwise never be seen here. It also held an archive of British labour movement films of the 1930s, entrusted to its care by Ivor Montagu, who had collected it (and made some of them himself). Some dozen years ago, I secured a research grant to work closely with Stanley to create a database of the collection. Our little team went through all the index cards and the films themselves, entering the metadata, which is when I really discovered its riches.*

I first met Stanley in the mid-1970s, through solidarity work with Chile. Three years after the military coup, I found myself curating a season of films from and about Chile at the old NFT, and some of them came from Stanley. We hit it off together, and he asked me to direct a documentary he was producing for Chile Solidarity—we even started, but I had to pass the film on to someone else when I had a car crash which put me out of action for three months. The warm friendship we struck up came in part from cultural affinity—and a shared sense of humour. Stanley was born to a Jewish immigrant family in the East End of London in 1921, he was politicised in his teens by the turbulent 30s, and joined the Young Communist League at the age of 15. In short, he exemplified the secular Yiddish radicalism of my parents’ generation, and our conversation was often punctuated ironically by Yiddish words and phrases. But if Stanley was proud to be Jewish, he also once told me of the problems this entailed soon after the war, when he was supposed to go on a trip to Moscow for the first time, and was refused a visa. Ever cheerful, he never shied away from talking about the most difficult questions, including the inevitable ‘But why did you never leave the Party?’ To which his simple answer was, how could he? ‘The Party becomes your family.’

I first met Stanley in the mid-1970s, through solidarity work with Chile. Three years after the military coup, I found myself curating a season of films from and about Chile at the old NFT, and some of them came from Stanley. We hit it off together, and he asked me to direct a documentary he was producing for Chile Solidarity—we even started, but I had to pass the film on to someone else when I had a car crash which put me out of action for three months. The warm friendship we struck up came in part from cultural affinity—and a shared sense of humour. Stanley was born to a Jewish immigrant family in the East End of London in 1921, he was politicised in his teens by the turbulent 30s, and joined the Young Communist League at the age of 15. In short, he exemplified the secular Yiddish radicalism of my parents’ generation, and our conversation was often punctuated ironically by Yiddish words and phrases. But if Stanley was proud to be Jewish, he also once told me of the problems this entailed soon after the war, when he was supposed to go on a trip to Moscow for the first time, and was refused a visa. Ever cheerful, he never shied away from talking about the most difficult questions, including the inevitable ‘But why did you never leave the Party?’ To which his simple answer was, how could he? ‘The Party becomes your family.’

For many years, Stanley distributed documentaries on all sorts of subjects—scientific, instructional and cultural as well as the more obviously political—to groups such as the British-Soviet Friendship Society, schools, the peace movement and even sometimes the army. There’s a rich font of research for someone’s PhD in the records that were kept of feedback from the people who booked the films, and indeed the history of Plato/ETV all told includes revealing episodes. In 1958, a film by the now forgotten East German documentary team of Andrew and Annelie Thorndike, called Operation Teutonic Sword, caused an international rumpus by revealing the Nazi past of the then commander of NATO ground forces in Europe, one General Speidel. Speidel sued Plato for libel. The case took three years to go through the courts and reached the House of Lords on a legal point. Eventually Speidel settled out of court, renouncing financial claims in return for the film’s withdrawal from circulation. Stanley said ‘We never lost, we never won.’ But he took the precaution of shutting down Plato and setting up a new company called ETV.

The legal issue concerned is an interesting one from a theoretical perspective. The problem, in a nutshell, was that British law would not accept proof made up of photocopies of documents discovered by East German spies in Bonn. Perhaps you can’t blame them, but the affair revealed the blinkered view of legalistic judgment over the nature of documentary film evidence, simply because the judges had to allow the possibility that something seen on the screen might have been faked, regardless of the context.

Plato/ETV’s operation was possible because it didn’t have to pay for the films. They arrived through the channels of the international friendship societies, that’s to say, shipped in through the diplomatic bag—the embassy in question would then call up and send them over. (This meant that Stanley didn’t always know exactly what films he held.) With the switch from film to video for educational and cultural distribution, ETV managed to survive because the passage of time had another effect: it turns a film library into an archive, a resource for filmmakers producing a growing number of historical documentaries, who used it well enough to keep the company going, as well as others, like film historians. Fully aware of the riches stored in his offices in Islington (and in his loft at home), he gave open access to students, and generously allowed me to take digital copies of a few films I wanted to use for a documentary I later made about a relative of mine who was closely involved in the electrification of the Soviet Union. I could not have made this film otherwise. Archives are places where things get lost and then rediscovered, and it was in Stanley’s archive that I found crucial footage: a wonderful forgotten film made by Esther Shub in 1932 called КЩЕ, or ‘KShE’ (Komsomol, Patron of Electrification), which I’ve written about elsewhere.

Saddened to hear the news of Stanley’s death, I soon found myself smiling at many fond memories. In the Q&A after a film screening, voicing exactly my own criticism of the film we’d just seen but with devastating politeness. In the music room of a mutual friend who lived down the road from him, a musician who’d invited us all to come and celebrate a Schubert anniversary with a real live Schubertiade. But one of these memories is particularly wistful today. I see him in his office in Islington, telling me about speaking at the funeral of a comrade the day before, the second or third such occasion in a row, and saying, ‘I’m thinking of putting a small ad in the Morning Star: Stanley Forman, specialist in Communist Funerals.’ He now goes to join his comrades in history, leaving us, in the archive he curated, with a history to ponder over.

* The archive is now held by the BFI; some of the films can be viewed through the JISC Media Hub (jiscmediahub.ac.uk).

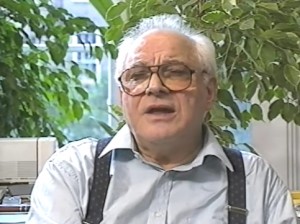

Photos from ‘It’s a wonderful life’ (Martin Smith, 1994)

3 Responses to Remembering Stanley Forman