When the issues become too sharp and the contradictions too blatant, the news media are severely challenged to contain them within normal bounds. They generally try to keep stories apart in order not to have them contaminate each other, but just recently this became impossible. The events in Gaza and Ukraine are not directly connected, yet in the mediasphere they became coupled by their coincidence in time and their jostling day by day for the top story slot. As a result, it was impossible not to see, for example, the shameless hypocrisy of the British Prime Minister berating France for selling warships to Russia while everyone’s military support for Israel continues unabated. In Britain’s case, it has emerged that the value of all British military exports to Israel currently being processed stands at £7.9 billion, including a single deal last year worth more than £7.7 billion for cryptographic technology.

Then the two stories got joined up. While Israel rained down state terrorism on Gaza, the media were focussing on why flight MH17 had been allowed to overfly a zone of armed conflict, until one of Hamas’s rockets landed close to Israel’s international airport and most of the foreign airlines serving the route announced a suspension of flights. A perfect example of the way the media are sucked into the fears that they themselves have a large role in generating.

There was a massive disparity in the coverage of Gaza and the Ukrainian air disaster, to the disadvantage of the former. Could the reason be, asked a letter in The Guardian, ‘that the western nations, and especially the US, see it as in their interest to prevent public concern over events in Gaza from reaching a point where they might be forced to put pressure on Israel, whereas arousing popular feeling over the tragedy of MH17 can be seen as an excellent means, literally dropping out of the sky, of putting pressure on Russia?’ Good question, but how should a phrase like ‘the western nations’ be construed? It isn’t nations that behave like this, but governments, and the corporate media who follow their cues. The various ways this kind of news management happens is something to think about, but for sure it’s systemic.

There is also a marked disparity between the space given to the Israeli and Palestinian points of view, with the former being hugely favoured, and another letter on the same page observes that the misreporting on Israel has been going on for a long time. (The Bad News team in Glasgow brought out two books demonstrating the process, in 2004 and 2011.) This time round, however, the veil is beginning to tear. A contributor on MSNBC broke ranks on air, accusing the network of a pro-Israel bias:

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I-j-iUwaykQ[/youtube]

The same charge has been made against the BBC, with 45,000 people signing an online petition, and hundreds turning out to protest in London and cities across the country. (Also here.)

The Guardian columnist Suzanne Moore worries in a woolly sort of way that the ‘endless pictures of dead toddlers’ circulating on Twitter are no help. ‘How many pictures of dead children do you need to see before you understand that killing children is wrong?’ A better guide to the effects of the social media is provided by Channel 4 (formerly BBC) correspondent Paul Mason, who writes in a blog about ‘a massive change in the balance of power between social media and the old, hierarchical media channels we used to rely on to understand wars’. The social media, he says, have the power to do three things. First, they show a version of events that is independent of the TV networks. Secondly, journalists on the ground now themselves employ social media (you can see this at the start of the MSNBC report below), which short-circuits the editorial processes that normally filter what gets said and reported. Third, as if in answer to Moore, the social media ‘get into your real life consciousness much more powerfully than the old media.’

The first of these effects derives in large part from the citizen journalism that is now an integral part of virtually every site of conflict around the globe, which not only circulates through the social media (though language remains a barrier in the borderless virtual world) but upon which the kleptomaniac news media have become increasingly dependent. This includes videos shot by Hamas. Below the media radar, the internet also provides the tools for international solidarity, the organisation of campaigns and protests, etc., feeding the numerous international protests against the latest Israeli actions, and the expanding BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) movement, whose growing strength has become a serious worry to the Zionists. But what do you know, the Israeli military has a specialised unit for intervention in the social media, adept at targeting critical or oppositional websites by underhand means like DNS attacks. One friend of mine reports that his site has been brought down a number of times. At the start of the latest intervention in Gaza, a call was issued to students to join in the work of this unit, offering them a not insubstantial fee of $2000 for the job.

The second effect threatens the breakdown of effective editorial gatekeeping. A case in point is that of NBC and Ayman Moyheldin, who was recalled from Gaza after filing a powerful report on the killing of the boys on the beach, with whom, by chance, he had been playing football a few moments earlier:

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pie6NAVPSaU[/youtube]

When Glenn Greenwald reported his removal on The Intercept, the social media kicked in with a large number of protests, and NBC climbed down and re-instated him. If this is an effective demonstration of social media as a medium of local political intervention, it was also the internet that helped to get him into trouble to start with, so what we see here is an instance of the internet’s multiplication effect. Moyheldin had come under attack on neocon and pro-Israel websites as a ‘Hamas spokesman’ who spouted ‘pro-Hamas rants’, for reports which Greenwald describes as ‘far more balanced and even-handed than the standard pro-Israel coverage that dominates establishment American press coverage; his reports have provided context to the conflict that is missing from most American reports and he avoids adopting Israeli government talking points as truth.’ Lack of context and taking the Israeli government’s word as truth are two of the complaints against the BBC.

Mason’s third effect is couched rather vaguely, but he’s thinking of the ‘subliminal and pervasive nature’ of the content that ‘floods people’s timelines’. No doubt some of the effects of this digital ticker-tape are indeed subliminal, but more immediately, the content it carries is in your face. Speaking as a news junkie, my Facebook and Twitter feeds not only serve for diversion and keeping up with far-flung friends, but have long become alternative sources of news. They provide a continuous supply of photos and videos from Gaza itself, as well as solidarity messages, reports of protest demonstrations, articles one might have missed in the press, and so forth. The days following the start of the Israeli attacks were remarkable for the degree to which everyone everywhere (from California to Chile to India) was being mobilised by the suffering in Gaza, almost to the exclusion of anything else. Of course the sources in your feed are your own selection, and pundits warn of the danger that this only reinforces the prejudices you start with—as if this were not true of your choice of newspaper or TV news channel—but that’s not the issue here. As a Jewish friend puts it in a post on Facebook: ‘I have found that Zionists generally are quite delusional and like other such people (born again Christians, Muslim fundamentalists, Ukip or Tea Party supporters) not the least bit open to consider any views which call into question their ‘core’ beliefs.’

Nor is the constant traffic just an effect of contagion—another generalisation, which too easily belittles the widespread anguish and anger over what is happening. But if this global swell remains limited in political effect, as much cyberpolitics is bound to do, it nevertheless expresses the urgent need for it.

Despite the constraining ideology of the mainstream news media, it makes a difference that their reporters are there on the ground. Moyheldin, one of a small band of network journalists reporting from Gaza, filed an unusual piece about how they get there, through the heavily fortified border crossing at Erez.

After traversing the kilometre-long wired-in walkway to the Hamas checkpoint on the other side, he comments that ‘you can understand why some human rights organizations call Gaza “the world’s largest outdoor prison”’. He adds: “One of the major complaints and frustrations among many people is that this is a form of collective punishment. You have 1.7 million people in this territory, now being bombarded, with really no way out.” The same points are made in a magazine column by the BBC’s Jeremy Bowen where he also writes about Erez, and despairs that no peace deal seems possible, and no-one knows how to put out the fire that is burning across the Middle East.

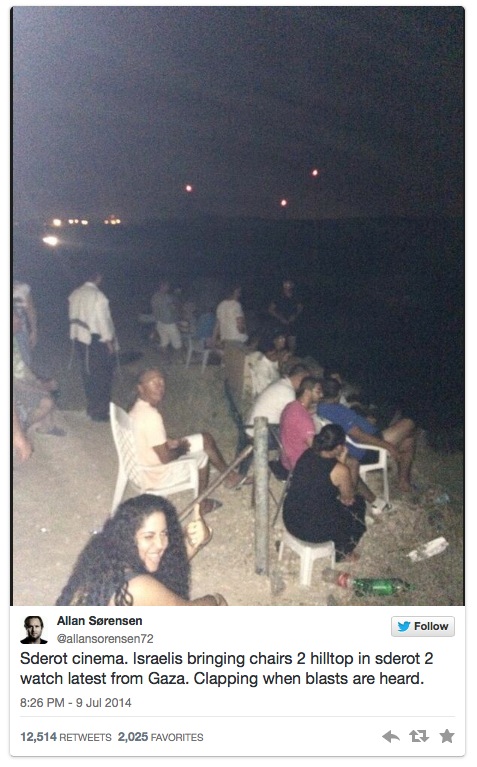

There is little room for background, context, history, and a couple of short animated videos circulating through YouTube, however well-intentioned, are too schematic to help much. The Bad News books, however valuable, are empirical studies, and the reasons behind the bias they demonstrate are rarely discussed. Discussion is discouraged by the ‘subliminal and pervasive nature’ of what some years ago Norman Finkelstein called ‘The Holocaust Industry’—the trade in movies and books, the museums and memorials dedicated to the Shoah—whose soul has long been appropriated by pure propagandists. The awkward question is posed, however, in a brave piece by the columnist Owen Jones on ‘How the occupation of Gaza corrupts the occupier’, which starts by citing the atrocious ‘Sderot Cinema’, a hill above Sderot, overlooking the northern tip of the Gaza strip, where Israelis were gathering to watch and whoop and cheer the bombs and explosions of the Israeli onslaught, in what a Danish newspaper described as a kind of ‘reality war theatre’; and which illustrates, says Jones, ‘how occupations corrupt the occupier’.

Looking behind the repulsive image, Jones finds a simple, fundamental truth (well, no, it isn’t simple, it belongs to the DNA of the Zionist State): ‘The moral corruption that comes with any occupation has fused with the collective trauma of the Jewish people’, or as a human rights activist in Tel Aviv expresses it: ‘In Israeli society there is a victim mentality that is deeply, deeply rooted in the Holocaust and encouraged by those in power’. This becomes self-righteous rejection of criticism, as if to say ‘We’re not racist. We are the victims of racism. Now we can defend ourselves, we will—and celebrate the fact.’

If this is to approach the perilous territory of the collective psyche, meanwhile the Holocaust industry combines with the Israeli state apparatus to counter the political critique of Zionism. Former US President Jimmy Carter, echoing South Africa’s Bishop Tutu, earned their ire in 2006 for his book Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, but the building of the infamous wall around the West Bank begun in 2003 bears out the criticism of the Zionist policy of segregation. The aweful irony is that a wall has two sides, and it’s also as if Israel has built a wall around itself. Instead of seeking to co-exist in peace, Israel has re-created the ghetto. And then created a ghetto within the ghetto.

Four years earlier, the great Portuguese writer Jose Saramago went further, and was pilloried when he visited Palestine as a member of an international writers delegation, and then told the radio back home that ‘What is happening in Palestine is a crime that we can compare to what occurred in Auschwitz.’ Yet according to an Israeli newspaper at the time, an Israeli officer was busy advising his troops to study the tactics adopted by the Nazis in the Second World War, ‘If our job is to seize a densely packed refugee camps or take over the Nablus Casbah…an officer…must…analyze…the lessons of past battles even…to analyze how the German army operated in the Warsaw ghetto.’

What Jones doesn’t go into is that the victim mentality finds its counterpart in the unspoken guilt complex of the Western nations towards the Jewish people, who, living among them, had been persecuted since medieval times, until antisemitism reached its horrific but logical conclusion in Nazi Germany. This suppressed sense of guilt becomes a hidden shame which forbids the expression of anything that could be construed as antisemitic,  but cannot distinguish between Jew, Israeli and Zionist, as if you cannot be only one of these. To which my response, as an English Jewish Anti-Zionist, is ‘Not In My Name’. Or the name of my grandparents who perished in the Warsaw Ghetto.

but cannot distinguish between Jew, Israeli and Zionist, as if you cannot be only one of these. To which my response, as an English Jewish Anti-Zionist, is ‘Not In My Name’. Or the name of my grandparents who perished in the Warsaw Ghetto.

The same sentiments have been expressed by the veteran Jewish Labour MP Gerald Kaufman, whose parents came to England as refugees from Poland. Urging the government to impose an arms embargo on Israel during a House of Commons debate on the fighting in Gaza in January 2009, he recalled that his ‘grandmother was ill in bed when the Nazis came to her home town. A German soldier shot her dead in her bed. My grandmother did not die to provide cover for Israeli soldiers murdering Palestinian grandmothers in Gaza.’ For Kaufman, ‘The present Israeli government ruthlessly and cynically exploits the continuing guilt among gentiles over the slaughter of Jews in the Holocaust for their murder of Palestinians.’

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qMGuYjt6CP8[/youtube]

*

Amidst the constant noisy stream of the news, the truth arrives in tiny moments that cut to the quick. A man interviewed on Channel 4 standing in a rubbled-strewn street concludes: ‘This is a miserable life. This is not life.’ In a flash, the words make me think of Giorgio Agamben’s phrase ‘bare life’, in his book Homo Sacer. This is a dangerous thought, returning us to Saramago’s metaphor, which is maybe not a metaphor after all. ‘Bare life’ is Agamben’s term for the conditions of existence of people subjected to states of exception, detained in places where they suffer exclusion from the political community, where the rule of law is suspended, and life is reduced to biological survival. Where the state of exception becomes the rule, anything is possible. But this, Agamben insists, is a juridico-political structure, a legally recognised act of exclusion. It is not, for example, like the lawlessness of a failed state, or the struggle for survival produced by prolonged drought in Africa, say. It takes place within delineated borders, guarded perimeters.

The paradigm for this condition is the Nazi concentration camp, because they perfected it, but they didn’t invent it. It is a recurring feature of the modern world. Historians, Agamben tells us, debate whether the first to appear were the campos de concentraciones created by the Spanish in Cuba in 1896 to suppress the popular insurrection of the colony, or the ‘concentration camps’ into which the English herded the Boers toward the start of the century. The first concentration camps in Germany were the work not of the Nazi regime but of the Social-Democratic governments, which interned thousands of communist militants in 1923 on the basis of Schutzhaft, or ‘protective custody’, a juridical institution of Prussian origin allowing detention without criminal charge if considered a danger to the security of the state. When Himmler, says Agamben, ‘decided to create a “concentration camp for political prisoners” in Dachau at the time of Hitler’s election as chancellor of the Reich in March 1933, the camp was immediately entrusted to the SS and…placed outside the rules of penal and prison law, which then and subsequently had no bearing on it.’ In juridical terms, this means that the inmates can suffer death without anyone committing murder.

This contention provokes the self-righteous fury of hard-line Zionists, and exercises the pro-Zionist centre-left, who wishing to appear reasonable, are liable to counter by arguing that the comparison isn’t accurate, or what-have-you. No, Gaza isn’t Auschwitz, but it’s a place of ‘not life’. Where external law is suspended and the Occupier refuses to acknowledge an elected internal government, however repugnant it finds them. Where instead the Occupier’s forces apply an elaborate technique of ‘roof knocking’ to warn people to leave their homes, intended to demonstrate that Israel is behaving responsibly, when in truth there is no law which could possibly apply. People cannot flee in time, and anyway where would they go? And so they get killed, but no-one commits murder.

Or else you say, this is collective punishment, which is something the Nazis practised in the countries they occupied. And this can only make you weep.