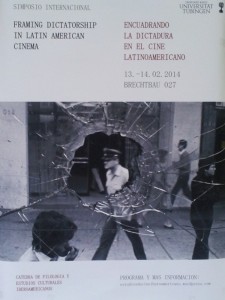

In the world of film studies, Germany is a country not much associated with the investigation of Latin American cinema, but here we were, gathering in the small university town of Tübingen for a Spanish-speaking symposium on ‘Encuadrando La Dictadura en el Cine Latinoamericano’—’Framing Dictatorship in Latin American Cinema’. It’s an odd sensation, going some place where you don’t speak the native language for a gathering that’s conducted in another language altogether. You end up addressing the waitress in the restaurant in Spanish—who then replies in Spanish, and you’re no longer quite sure where you are!

Convened by Sebastian Thies and intended as the founding event of a new (and peripatetic) Forum for Iberamerican Audiovisual Studies, the range of papers was impressive, with sessions on feminine militancy, testimonial, discourses of exile, violence on the screen, propaganda and power, memory and the archive, and the commodification of memory. The opening presentation, by Madalina Stefan and Daniel Villamediana, introduced a double concept of framing (using the English word) as the film frame which separates space into on and off screen, and framing as the conceptual organisation of experience, in Erving Goffman’s sense, which is social, cultural and collective. Both of course are subject to multiple logics, and a film is always composed of hybrid discourses.

The framework for the representation of the dictatorships is also double, history and memory, and there are several modes in which these can be brought to the screen, as we learned over the two days. Stefan and Villamediana suggested three characteristic phases, where you first get films of exile, then comes the construction of public memory, and more recently, those of the ‘postmemory’ generation. The construction of public memory in turn has had two phases. First come films of resistance, which aim to counter the dictatorship’s official propaganda and establish their own counter-hegemonic version. But in one of their most interesting suggestions, a second wave of films arise when belief in armed revolutionary struggle subsides, and collective militant filmmaking gives way to an auteur cinema which is marked by both the experiences of the dictatorship and loss of the utopian imaginary, to become an accented cinema. What makes this so interesting is the way it locates the change in the wider historical perspective of the end of the Cold War.

This is a rich and sophisticated schema. From the perspective of critical theory, the benefit of multiple frameworks is precisely that it allows you to shift the focus from one dominant to another. It also worked well for positioning the individual films which other papers discussed. Various contributions homed in on individual titles that raised particular issues in paradigmatic form. Markus Schäffauer talked about the resilience of torture survivors shown through a mix of documentary and fiction in Lúcia Murat’s Que bom te ver viva. Daniela Opitz spoke about the ‘re-enacting’ of women’s militancy in Gaby, la montonera by César D’Angiolillo. Christian Wehr examined cultural memory, historical experience and the messianic perspective of that masterpiece of exile cinema, Tangos, el exilio de Gardel by Fernando Solanas. Sebastian Thies himself considered El Acto General de Chile by Miguel Littin as a paradigm of the value of the ‘talking head’ testimony. Luis Pares came up with a striking discovery: a film shot in Chile in 1977, made for French television by exiled Spanish director José María Berzosa, in which the dictatorship’s politicians are given space to reveal themselves. In one scene, which brought a moment of levity to the gloomy subject matter, Pinochet himself sits smugly beside his wife on a sofa while the interviewer asks her to tell him about her husband, and she replies, ‘I’ll begin with his weaknesses… he’s a bit dominant…’

Others came at things from different angles (with apologies to those not mentioned): Rodolfo Franconi provided a lucid overview of the contradictions of Brazilian cinema over the twenty-one years of dictatorship, while Nina Schneider looked specifically at official Brazilian propaganda films of the period, which showed a marked modernisation over previous periods. But as Franconi put it, it was the uncensored soft-core pornochanchada that was more effective in giving people the impression of living in a free country. David Jurado looked at the use in different films of the footage of the bombing of La Moneda, the presidential palace where Salvador Allende’s life came to an end. Pablo Piedras (in a paper coauthored by Clara Kriger) presented a lucid analysis of the discursive treatment of archive footage in Argentine documentary, which despite their differences, and whether the archive is presented as evidentiary, indexical, illustrative or evocative, mostly seem to sustain an interpretation of the past which pre-exists the making of the film.

For myself, I don’t much like the term ‘postmemory’. Memory, especially the memory of trauma, persists in various ways, as I learned in making Interrupted Memory/Memoria interrumpida, a documentary about politics and memory in Argentina and Chile, which I was invited to present at the symposium. One of the things I found in making it was an echo in Chile of something I readily recognised from the experience of my own generation, Jewish children born just after the Second World War, which was a kind of reticence that affected the whole community, not just the families of survivors. The trauma of the Holocaust is collective. It not only affected the immediate victim but has serious consequences for the next generation, which endures the tacit absorption of what their parents’ generation cannot fully or properly communicate. There is a strong echo of this in Chile, where interlocutors spoke of ‘a veil between the generations’ which comes in part from ‘a difficulty in codification of what happened, giving it a name’, and in part from the reluctance of parents to speak of the pain and fear they experienced, not necessarily out of guilt or shame but in order to protect their children from it. The children, meanwhile, like the lads in the film occupying their high school, tell us that none of this in taught in school, and they have to find out elsewhere, including films and videos.

Argentina is different in this aspect, much more complicated, partly because the return to democracy came earlier, the enormous number of victims could not be suppressed but the fight for justice had to manoeuvre several stages, which exposed the fragility of the judicial system and raised questions about the character of political violence. But every country, as the symposium demonstrated, has its own political history to contend with. At the same time, each country generates its own official version of events, its own public human rights discourse, which is affirmed or contested in films both fiction and documentary. Perhaps it is right, as someone observed, that the relation of the present to the past is imaginary, but as Héctor Schmucler observes in Interrupted Memory, ‘memory comes before history—that’s how it is in mythology: Mnemosyne is the mother of Clio. Memory creates the space in which history works.’ But memory and history, he says, are not incompatible as long as the memory finds historical confirmation; if it doesn’t, it will fade. In this sense, the screen is a primary medium of social memory, at the same time agent, promoter, product and reflection of a cultural process which in reconstructing the past is produced by everyone and no-one in particular. Of course the individual film is the creative product of a certain author, but what it evokes in the spectator is no less collective for that, and even a film that is narrowly focussed takes place in social memory, which will make its own judgement.

And then there was this, leaving through Stuttgart airport. Who says Germans don’t have a sense of humour? But maybe it’s a little morbid: