Arriving in Buenos Aires the day after the Labour Party leadership election results were declared, I was impressed to discover that practically everyone I talked to during the ensuing week—whether economist, sociologist, journalist, workman or community activist—already knew Jeremy Corbyn’s name. My impression was that they also approved of his position that there is an alternative to the politics of austerity, which is something Argentina suffered in the closing years of last century and brought about the country’s economic collapse early in the new one. A couple mentioned the comment of Argentina’s ambassador in the UK that Corbyn is uno de ‘los nuestros’—’one of “ours”‘—in reference to the question of the Malvinas. ‘Is that really true?’ they asked me, and I told them he was no warmonger and advocated negotiation (like Tony Benn in 1982). This is for the future. Meanwhile there are others things to attend to, like the elections coming up in late October—about which I offer no comment: Argentine politics remain confusing and impenetrable even to Argentinians.

The purpose of the visit was to interview people for Money Puzzles, the film I’m making with Lee Salter, in order to find out about the Argentinazo at the end of 2001, when Argentina defaulted on its international debt—the largest such default in history—the banks closed their doors, and for a time there was no money in circulation. Taking time out to arrange everything was my very good friend and documentary filmmaker Guillermo De Carli; Alejandro Morín doubled as cameraman and taxi-driver.

Several people talked about what had happened, including Luis, a brickie (he was working on converting Guillermo’s flat) who was one of the demonstrators on 19 December 2001, reporting for a community radio station; and Daniel, an activist with Barrios de Pié (‘Neighbourhoods Standing’), an association for community solidarity set up at the end of 2001 to support the hungry and unemployed. The immediate aftermath was utter chaos, with people reverting to barter (trueque) to survive and provinces issuing their own makeshift currencies. Would Greece have been overtaken by similar turmoil if Syriza had opted to exit the euro instead of capitulating to Brussels? Almost everyone I spoke to had something pertinent to say about Greece, but mostly considered the situations of the two countries so different that direct comparison, they thought, was hardly possible. Even so, it’s very instructive in trying to understand the dynamics of a global economy which is driven by increasingly unpayable debt.

To understand the Argentinazo I spoke to two economists of different tendencies, and a sociologist, who between them provided a rich account of what happened and of the aftermath. First, the 87-year-old Aldo Ferrer, a strong economic nationalist whose venerable career includes spells as Minister of Economy, governor of a major bank and Ambassador to France, alternating with academia; and then Jorge Beinstein, a Marxist academic with strong Latin American links and a long standing interest in globalisation and what he’s called ‘senile capitalism’. The sociologist was Alcira Argumedo, one of the co-founders in 2007 of Proyecto Sur, the left-wing party led by filmmaker Fernando (Pino) Solanas, for which she was elected a Deputy two years later. Her association with Solanas goes back to the late 60s, when he’d just made La hora de los hornos (Hour of the Furnaces), and she collaborated on Memorias del Saqueo (Social Genocide, 2004).

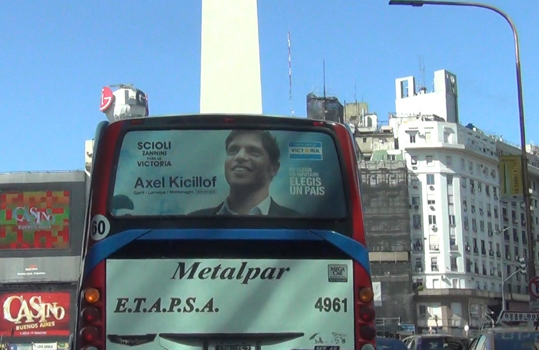

Economic recovery came quickly enough after Nestor Kirchner was elected President in 2003 and negotiated the restructuring of the debt with practically all the creditors, except a couple of vulture funds in New York who have been causing trouble in the US courts. But the whole issue has now moved to the arena of the UN, which only a few weeks ago approved what are described as global ‘basic principles’ for sovereign debt restructuring. Pleading Argentina’s case in New York has been the young economist whom the outgoing President Cristina Kirchner appointed as Minister of Economy a couple of years ago, Axel Kicillof, and the last of my interviewees (literally, because our twice-postponed meeting finally transpired at his home on Saturday morning a couple of hours before I had to leave for the airport).

A Trotskyist student militant in the ’90s, who helped to found a teachers union at the University of Buenos Aires, his writings, according the New York Times, use Marxist concepts to interpret Keynes. The deal was that I wouldn’t be asking him about the present political situation in the run-up to the elections in which he’s standing as a candidate for the Chamber of Deputies (I had given a similar assurance in Greece last May to Costas Lapavitsas, at the time a Syriza MP). I found him lucid and informative, and he didn’t bandy words in his critique of the IMF and related issues.

Now begins the long job of translating these interviews before starting to edit the Argentina chapter of the film—not to mention a trip to film in Spain at the beginning of November, and a good deal more filming here at home.