confidential occupations document – april 2009

The following leaked document had disappeared from the public domain due to the website which it was previously hosted on going down. It is a briefing for heads of university administrations on dealing with student occupations. It may assist activists in gaining some idea of the perspective of senior university officials on occupations – although some of the material is more specifically about occupations around Palestinian issue.

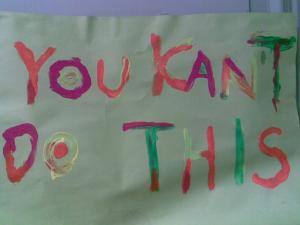

Sign at the occupied Middlesex Philosophy Department, 2010

Original introductory note by an ‘Education Not for Sale’ activist

What follows is a briefing published by university administrators concerning student occupations . It outlines some of the tactics used by university authorities to deal with student protest, specifically occupations. It is not clear exactly who wrote the briefing, or who received it, but since it is addressed to members of the Association for Heads of University Administration (AHUA), we can reasonably assume that it has been received by a number of vice chancellors and others in positions of authority around the country.

It was decided to publish this document at and Education Not For Sale open steering meeting on September 20th. There were no objections from the activists present.

A few activists have a hard copy of the document, and I have typed up exactly what is written on the actual document in our possession. What follows is my typed copy.

CONFIDENTIAL

Student Occupations: a briefing note for members of AHUA, April 2009

Background

Following the Israeli attack on Gaza, which commenced in December 2008, there has been a spate of student occupations throughout the UK and indeed other countries. About 30 UK HEIs experienced occupations during the first three months of 2009. This wave of student protest has a number of important characteristics and this briefing note has been prepared to inform members of AHUA.

Form of Protest

The occupations have been undertaken by a relatively small core of students expressing concern about the situation in Gaza, usually under the title ‘Gaza (or Palestine) Solidarity Campaign’ or similar. Although the form of the protests has varied, there are a number of general characteristics. Normally the occupation takes place in a lecture theatre or similar open area rather than in the administration building or library. The students have called on individual universities to take action in support of the people of Gaza (scholarships for Palestinian students, educational materials to be sent to Gaza). Sometimes there has been a link to the issue of investments by UK universities that manufacture military products and a call to support an ethical investment policy.

The students bring with them mobile phones and laptops. The link to the internet and the ability to publicise via blogs or Facebook is probably the single most important development compared to previous student direct action. The publicity generated and the mutual support offered via the web has been critical in spreading the protest around the country. For this reason, the actions taken by individual institutions in response to the occupations have consequences for others, with protestors using alleged examples of where their demands have been met to encourage action elsewhere.

Most of the actions does not appear to have been organised via any official students’ union route. Indeed, the National Union of Students in mid February called for the wave of protests to end because the level of disruption had reached unacceptable levels.

Political activists, who may or may not be current students, have played a part in organising the occupations. The Socialist Worker Party and other ‘hard left’ publications or posters have been displayed prominently. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to dismiss the spate of occupations as merely the work of activists. The students involved seem, in the main, to express genuine concern about the issues raised, even if the mode of expressing concern is disruptive.

There is a great deal of material now available on the web, for example:

http://stopwar.org.uk/index.php?option=com_newsfeeds&catid=84&itemid=230

http://communiststudents.org.uk/tag/student-occupation/

The lengths of the occupations have varied, depending on part whether the occupiers believe some or all of their demands have been met. In most cases the occupations have been peaceful, and relatively small scale. However, in a small number of cases they have caused severe problems.

Legal position on trespass

Our legal sponsors, Martineau, have prepared a note on the legal issues on trident occupations which is attached.

The legal position on trespass is complex and the following brief summary should not be regarded as a substitute for professional legal opinion. Further, the law on trespass in Scotland differs significantly from elsewhere in the UK.

In English law, trespass is a civil tort and is not normally an offence under criminal law. Students normally can enter lecture theatres or similar spaces and the university has to inform the protestors that it regards the occupation as a trespass. It is possible to seek a High Court injunction and claim for possession but the process is expensive and could reasonably be expected to take a couple of days. Under common law, a landowner (and for the avoidance of doubt, buildings are land) can physically evict a trespasser who refuses to leave provided that no more force than is reasonably required is used. In at least one case this was the action taken by an HEI to end the occupation. It is would be [sic] sensible to adopt this action only with the support of the local police who could be invited to witness the eviction. There are occasions when trespass might become aggravated trespass and the police could remove the protestors. This could occur in the event of criminal damage or if there is a threat of violence.

Difficult Issues

Regardless of the cause of the protest, HEIs will wish to minimise the disruption. Dealing with the occupation is likely to be time consuming and put particular strain on the campus security team.

Any issue relating to the Middle East is likely to raise the concerns of Jewish students and there has been a reported rise in hate crimes against the Jewish community over the past few months. The protestors have tried to make clear that they are not raising religious or race issues but the relationships are complex and not easily separated. Representatives of the Jewish community have urged individual universities not to concede to some of the demands made by protestors. Other students too have expressed frustration at the disruption caused by a very small minority, especially when there are suspicions that non-students are involved. The Universities UK media release on the situation in Gaza is a useful starting point for any university that would wish to make a public statement. It is available at:

http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/newsroom/media-releases/pages/gazastatement.aspx

However, even this has raised concerns from members of the Jewish community, specifically on the grounds of accuracy relating to the deaths in educational establishments.

Options for dealing with an occupation

- Refuse to negotiate and require those occupying to leave. This could be enforced by legal action. This option has the advantage of ensuring the university does not appear to concede to direct action. It assumes that the protest will peter out. However, it can result in the occupation becoming drawn out. A local judgement is required on the strength of the protest. It is possible to use the threat of internal disciplinary action against students. Most HEIs will have, as part of their disciplinary procedures, an offence relating to disrupting the normal work of the university or something similar. However, threat of legal or disciplinary action would be time consuming and difficult. It might not be easy to identify the students involved, who probably would not be keen to co-operate in such a process.

- Negotiate a settlement. Most universities appear to have been willing to talk to the protesters, issue a statement about the situation in Gaza and take some limited further steps. This has helped to bring individual occupations to an end relatively quickly but not before the protestors have had time to publicise their cause. Indeed, the publicity means that it is unlikely that any occupation will be ended within a brief period of time even if the university is willing to negotiate in good faith. In some cases, it appears that the original organisational energy is not sustained post occupation and the follow up actions are not pursued as rigorously by the students.

- Refuse to negotiate whilst the occupation is going on but express willingness to enter into negotiations after the direct action has ended. This course of action runs the risk of falling between stools. It is difficult to maintain the line of no negotiation whilst the occupation is in progress and some form of talks about talks are probably inevitable. Nevertheless, it does hold out the prospect of ending the occupation relatively quickly whilst preserving the HEI’s position of not conceding to the occupation itself. This, though, is a fine distinction.

Consideration should be given to the potential role of the students’ union in resolving the dispute. In some cases the officers have been rather distant, aware of their obligation to represent the broad community of students, but in others the officers have been involved as helpful intermediaries.

One important issue to consider is the access to the area being occupied. In some cases, the students concerned made clear that they would be willing to allow lectures to continue in the same room. They probably regard this as a way of minimising the threat of legal or disciplinary action. Consideration needs to be given early on to the policy the HEI will adopt on access to the area. If it allows free access, there is a risk that the occupation will lengthen, more people could join and it allows the protestors to rotate. The alternative is an attempt to control access. This raises allegations of heavy handedness by the institution. A particular issue is whether or not to allow further supplies of food into the building. Again, refusal to do so runs the risk of publicity being generated about the institution attempting to ‘starve’ the students out. It is important for the HEI to emphasise the priority of health and safety issues. Obviously, access to toilet facilities and an attempt to maintain reasonable conditions should be a priority both for the protestors and for the HEI.