Here comes another film on Che Guevara. This time it’s a documentary with the somewhat naff title of Chevolution, directed by Trisha Ziff and Luis Lopez, opening at the ICA in London on 18th September. In fact there’s been a constant stream of films, both dramas and documentaries, about el Che for several years now, and the only other twentieth century historical figure who has possibly had more films devoted to him over the same period is Hitler. Which makes you think.

Not long ago I found myself writing a decidedly unfavourable review of Soderbergh’s Che Part One (I never got to see Part Two), for its lacklustre script, odd omissions and flat pace. Before that there was Motocycle Diaries (‘Diarios de motocicleta’, Walter Salles, 2004) which although all very swish and commercial comes back to mind after the Soderberg film as a pretty good rendition of Che’s early politicisation. Salles had the advantage of the beautiful Gael García Bernal as the young Ernesto, before he got his nickname, who therefore had a certain freedom to invent the part. But the character is clearly a challenge for a certain kind of Hispanic actor, and Soderbergh’s Che is Benicio del Toro, who also produced the film, and turns in a very professional performance. (García Bernal makes a brief appearance in the new film as himself.)

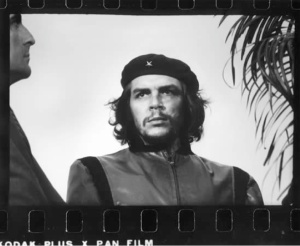

There have also been several documentaries, including a C4 ‘Secret Lives’ episode in 1995, and in 1999, an intriguing episode of the BBC’s ‘Arena’, called Who Owns Che? directed by Leslie Woodhead. The latter has much in common with the new film because they both focus not on Che the man and his politics, but on the image—in particular, the famous and iconic photo in which, as Richard Gott once put it, Guevara gazes ‘fiercely into some distant horizon’; an image which the BBC film calls ‘more universal than Elvis, as inescapable as the Mona Lisa’. And both films go back to the man who took the photo, the Cuban photographer Alberto Korda, although here the earlier film had the advantage because Korda was still alive and they were able to ask him about it.

Both films recount how the photo lay neglected until 1967, a few months before Che met his end in Bolivia, when the Italian left-wing publisher Feltrinelli, who was about to publish Che’s writings, came looking for publicity material, and Korda pulled it out. (Chevolution includes a nice account of the event by the Cuban photographer José Figueroa, who was then Korda’s lab assistant and had the job of printing them up.) The nub of the matter is that in those idealistic early years of the Cuban revolution, enthused by Che’s moral example as well as Fidel’s oratory, it didn’t occur to Korda that even if the Italian was a comrade, he came from a capitalist country and you ought to protect your copyright. Copyright didn’t exist in Castro’s Cuba, so he just gave it to him. Then after Che’s demise, Feltrinelli put it on a poster to advertise the book, and it entered world history. Both films mention that the poster failed to carry the photographer’s name but claimed copyright in the name of Feltrinelli’s firm. The new film has someone explaining that this was common practice in those days. The BBC film mentions that Feltrinelli was himself assassinated a few years later by Italian neo-fascists. Both films, by the way, make the point that ‘Che’ was a nickname given to Guevara by the Cubans, but the new film fails to explain why: because the word is Argentinian, a colloquialism for ‘friend’ (like ‘mate’ in English), which Che used in addressing others.

In fact the best account of taking the photo Korda gave on film is at the start of a short film made back in 1981 by a Chilean film editor in exile in Cuba, Pedro Chaskell’s Una foto recorre al mundo (‘A Photo Goes Round the World’). The photo in question is the same, prefaced by Korda’s reminiscence, and then seen in newsreel and documentary footage from around the world of the uprisings of 1968 and after. A true editor’s film, from which Arena borrowed some footage—without acknowledgement.

The photo dates from a protest rally in 1960 the day after a Belgian freighter carrying arms to Cuba was blown up by counter-revolutionaries while being unloaded in Havana harbour, killing over a hundred dock workers. As Korda recalled, it was a damp, cold day. He was panning his Leica across the figures on the dais, searching the faces with a 90mm lens, when Che’s face jumped into the viewfinder. The look in his eyes startled him so much, he said, that he instinctively lurched backwards as he pressed the button. ‘There appears to be a mystery in those eyes, but in reality it is just blind rage at the deaths of the day before and the grief for their families.’

When he printed it up, he cropped it so that there’s nothing in the frame except Che, against a grey background. The image becomes abstracted from its historical moment, and is thus ready to serve as a pure icon when its moment comes.

Both films have comments by the art historian David Kunzle on the religiosity of this icon, and how it draws on that other and highly dramatic photograph of Che’s body laid out by his captors on a slab for the press photographers—one of whom captures him from exactly the same angle as Mantegna’s Dead Christ. But only the new film turns this around in order to score ideological points, insisting that Che was no Jesus-with-a-beret but a doctor-turned-fighter who would rather abandon his medicine chest than his ammunition.

Feltrinelli’s copyright claim didn’t prevent it being copied freely in all manner of ways and on everything from posters and placards to stickers, graffiti, brooches, what have you; Cuba itself would use it on banknotes. The issue of copyright comes up in both films, of course. The new film takes the line that Korda was done out of huge potential earnings, although Korda’s daughter says they’re only concerned that it shouldn’t be used for improper purposes like advertising. The BBC film is better. Although shorter (by half) it allows space for ruminations by both Kunzle and an intellectual property lawyer, Alice Haemmerle, who considers the question from various angles, like commercial exploitation of the image as against intellectual property rights, but also speaks of the public ownership of iconic images and their use to make political, cultural, expressive statements.

In any case, Korda had no remedy until Cuba rejoined the international copyright convention in the 1990s, and thereby hangs a tale which isn’t told in either film, although the BBC film concludes by mentioning it. Korda began to try and pursue improper uses of the photo, which required legally establishing his copyright. When the image appeared in a Smirnoff advert in the UK (Che never drank) he decided to take action, and the Cuba Solidarity Campaign helped him successfully sue Smirnoff’s advertising agency Lowe Lintas and the picture library Rex Features for infringement. By happy coincidence, he received the news of an out-of-court settlement on his birthday, during a visit to London for an exhibition of Cuban photography—and immediately handed over an undisclosed sum for damages to buy much needed medicine for Cuban children.

The worst thing about the new film is the music. Where the BBC film puts together a soundtrack of appropriate latino vocals, Chevolution fills every available space with the synthetic rhythms of recent fashion, to accompany a dazzling array of synthetic digital effects on the screen. The effect is to expose the film’s lack of historical sense. The problem is the result, I gather, of its complex history of production. What started out with a small independent London-based producer reaches the ICA with seven executive producer credits and four production companies. The result is a film that bears the stamp of no identifiable author, where the issues are fudged and you can’t tell who’s responsible. Or perhaps the truth is that the iconic power which the image of Che Guevara continues to exert is, like his opposite the Nazi dictator, just too big to nail down.