On Friday, here on the riverside at Putney, they started setting up the outside broadcast cameras for the Boat Race, the annual jamboree when Putney gets to be briefly seen on screens around the world. A strange object appeared looming up over my house.

On Saturday, came reports that an unexploded WWII bomb was discovered near the bridge at low tide, near the starting line, but it was expected the race would still be going ahead. This was confirmed after the object was revealed—and retrieved—at low water on Sunday. (Meanwhile, somewhat ironically, with the recent Westminster attack still fresh in the memory, the police urged the expected tens of thousands spectators to be extra vigilant.)

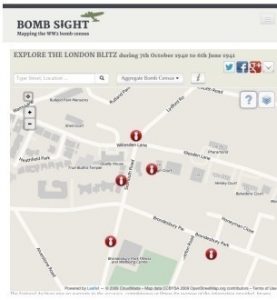

Oddly, there was another report, just one month ago, of an unexploded bomb being found in the same street where I grew up in north-west London. The coincidence takes me back to a moment around five years ago, when the Guardian published an interactive map on the web showing the locations of bombs which fell across London during the war: it indicated five of them close to where we lived. I have a strong memory of a bombed site on the corner, though not quite in the same place as marked on the map, and wondered if my brothers, all three of them older than me, would remember others. A few days later we were lunching together, as we do every now and again, so I printed out the page for where we lived and took it along.

D., who was thirteen or so when we moved to Brondesbury Park after the war, seemed surest about his memory, but thought the site had a garage built on it later. I remember a garage, but not quite in the same place. In fact, none of us could agree on what the map showed. All of us were puzzled by one location in particular which looks on the map like it was at the bottom of our garden, and there was no bombed site there, only the garage with the flat upstairs, in differently coloured brickwork, where an old couple lived who used to invite us in for refreshments. Nonetheless, the bomb find a month ago does rather confirm that quite a lot of them must have fallen around Willesden Green.

This would not be news to the good doctor Oliver Sacks, who grew up a few streets away, and in his autobiography Uncle Tungsten, remembers a bomb falling next door in 1940. Actually two bombs, but after the book was published, his brother told him the second memory was false—they were neither of them there: they’d been evacuated. However, their other brother had been there and described it in a letter to them. Sacks concluded that he’d adopted the letter as his own memory. But he also believed that there’s no such thing as fixed memories, only the act of remembering.

There must be many ways in which the memories of events shared by siblings fail to coincide for different reasons. I have another example of memory discord among the four of us revealed indirectly through a report in the media of an historical event. First comes a personal memory. A fantastic storm is blowing and I’m just inside the back door which is being lashed by the tremendous rain, I’m jumping up and down flaying my arms and crying out for my mummy at the top of my voice. I can’t be quietened even by my auntie J., until, I guess, I’m exhausted. I associate this with the day the house was hit by a tornado which tore a good many slates off the roof, so that the builders had to be called in and the house swathed in scaffolding for repairs.

A tornado in London? I can’t be sure I haven’t conflated two different memories, but the tornado turns out to be real enough. In December 2006, a freak tornado hit the nearby neighbourhood of Kensal Rise, ripping roofs off houses and uprooting trees; half a dozen people were lightly injured and hundreds left homeless. I noticed the story in the news precisely because of the memory it evoked. A few weeks later, a television programme about extreme weather in England compared it to a previous occurrence, when a tornado ripped across north-west London in December 1954. Which means I would have been eight. The television programme enabled me to corroborate a personal memory, but at another brothers’ lunch, when I asked them about it, none of them could remember. Since the event in question was for real and obviously dramatic, we had to stop and work out why not. Easy in the case of G., whom we quickly concluded was away at boarding school, and D. who wasn’t living at home any more. The mystery is why N. didn’t remember it.

No solution to this puzzle. Memory is not only about remembering. It is also about forgetting.