At the bottom of this long, pitted and dusty road in Athens is the Eleonas refugee camp, located in a run down industrial estate. This is my only picture because we weren’t allowed to film or take photos inside the camp, which currently houses around 1600 refugees from many different countries, but mainly Afghanistan and Syria. More are expected.

The visit, on a Saturday afternoon, was part of a workshop earlier this month on Modernization, Europe and Nation-State at the Panteion University, which I was invited to attend in order to show the chapters on Greece from our forthcoming film, Money Puzzles. The screening elicited a rich discussion about the nature of money.

The prohibition on taking pictures at Eleonas was completely understandable, albeit frustrating, since I always carry a small camera with me just in case. But the residents of a refugee camp are not exhibits, and some are afraid of being recognised. However, I found the role of academic tourist uncomfortable, and had to ask myself why I prefer that of documentary filmmaker. Not a question susceptible to an easy answer, though I’ll say that it offers the pose of not being a tourist.

Eleonas, we were told, is the best organised of the 25 refugee camps in the country. We were shown around by Mahmoud, born in Greece of a Sudanese family, a modest young man employed by the government to run the camp’s educational programme, which includes language classes. The refugees, who have been there for several months, are housed in containers equipped with electricity, sanitation and drinking water, in which conditions are cramped – two rooms in each container with four beds in each. But the camp has plenty of open spaces, a football pitch, and some large tents, laid out as play spaces which also serve for cultural activities, including film shows and visits from music and theatre groups. Everyone gets three meals a day, supplied by the Greek Navy, as well as medical and dental care and assorted services like translation, with different government departments responsible for different services. There is a UNHCR office.

Some 40% of the camp’s population are children. There are play groups but no schooling, although around forty of the children have started attending local schools. The camp is lightly guarded by the police and the residents are free to come and go – they just sign in and out. Although some have now begun to apply for asylum in Greece, most of them still hope to get to Germany. But after the EU agreement with Turkey, said Mahmoud, this was looking very unlikely.

Among the papers at the workshop, two in particular shed light on what we were unable to see on our visit to the camp. Under the witty title ‘To whom are the Greeks bearing gifts?’, Georgios Agelopoulos (an anthropologist from Thessaloniki who had organised the visit to Eleonas) spoke of the motivations of the many Greeks involved in active solidarity with the refugees. He told us, for example, of an elderly man who remembered the experience of his uncle, himself a refugee who came to Greece in the exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey in 1922. For this man and many others, the sense of solidarity is deeply rooted in family and popular memory. And then the succinct comment from the floor at a meeting of a neighbourhood branch of Syriza in Athens: ‘We support the refugees not only because of humanitarian reasons and our leftist ideology but also to prevent the skatopsichoi from taking control of the country’ – skatopsichoi, literally ‘having a soul made out of shit’, refers especially to Golden Dawn, who extend their own solidarity only to Greeks.

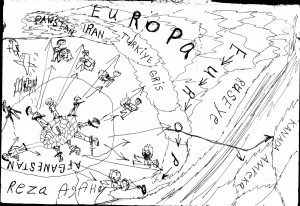

Then Evgenia Iliadou, a doctoral student at the Open University, presented her ‘Reflections from a detention centre in Lesbos Island’, which included the most remarkable of images – not a photograph but a map.

Drawn by a refugee from Afghanistan, a young man who arrived at the detention centre for undocumented migrants in Pagani, on Lesbos, in 2008/9, it illustrates the journey he plans to take from Afghanistan to North America. Significantly, Greece is not placed within Europe, but sits next to Turkey as somewhere you have go through to get to Europe. Suddenly, seeing this drawing, you see how the refugee sees the world. A cognitive map if ever there was one, in which direction is inverted, the world is turned upside down, but a single gestalt jumps out at you, the perspective of the Other on our common world. A world we share unequally, because of powers and forces neither of us control, including the men with the guns who cause the problems and block the way. Who is to say which is the right way up?

Georgios reminded us of the scale of what is going on. According to the UNHCR, more than 880,000 refugees and migrants arrived in Greece during 2015, a number corresponding to 8% of the country’s permanent residents. What small country would be able to cope? Certainly not Greece, where austerity economics imposed by the unforgiving regime in Brussels has weakened the state, whose infrastructure is overstretched. Indeed Greece has been doubly punished, first by the continuing intransigence of the Eurogroup, and then by Europe’s miserable failure to deal with the refugee crisis. The EU condemnation of Greece last January for not controlling its borders only adds insult to injury. Meanwhile, it would be difficult to explain how the needs of those 880,000 have been met, were it not for the solidarity of the Greek people in the midst of their own misfortune.

The trip was a short one, and evenings were spent as they should be, enjoying excellent Greek food in good company in the warm evenings amid the crowds. But the crowds are subdued, and Athens now seems to me a deceptive place, where behind the urban bustle lies misfortune and poverty of a kind that is not supposed to exist in what is supposed to be European prosperity. I was not surprised to be told that the Greek people are now widely disillusioned with Europe.