This is a revised version, incorporating feedback received.

At the beginning of July, the EICTV, Cuba’s world renowned film school at San Antonio de los Baños was hit by a bombshell when the current director, the Guatemalan Rafael Rosal, announced his resignation, following revelations about corruption involving illicit sales of beer. Three members of the school’s workforce were arrested, but there’s no evidence that Rosal personally benefitted. According to Rosal himself, speaking to me in Havana before leaving for England with his English wife and children, he had been obliged to resign as a scapegoat for a practice that had been going on for at least fifteen years, and which had reached the point where it was heavily subsidising the school’s operation, which costs US$1.4m a year. No small beer. He didn’t mention to me that he was asked to resign by the student body.

The way it worked was this. The School purchased beer from the brewery, Bucanero, at 8 CUC per carton, which it was allowed to sell to students, academic and support staff for 16, or two thirds the official price. Alongside this recognised form of subsidy, a trade developed on the side whereby a quantity of beer was sold on by ‘coyotes’ or fixers for 19 pesos, who sold it to local bars and restaurants while pocketing the difference.

This much is clear, but little else. Apart from Rosal, everyone who spoke to me about the affair during my week in Havana, did so off the record, but all of them were interested to know what everyone else had told me because, as more than one of them put it, it’s like Rashomon—no-one is in possession of the whole truth. Which also applies to this blog: whatever is written here, there’s always another version. For example, according to Juanjo, a recently graduated student representative, responding to the original version of this blog, ‘The beer affair was only the tip of the iceberg on issues concerning the way the school had been managed in the past couple of years, and in no way was the main reason why the student body asked Rafa to resign. The administration didn’t officially ask him to resign because they did not have the power to do so.’

Rosal is himself a graduate of the school, and his allegation that this has been going on for fifteen years is based on his own informal knowledge. Nor does it come as a surprise to anyone who has spent time at the school as a visitor, teaching workshops, as I’ve done myself—it was not exactly a secret, though I can’t now remember on which of my several visits I learned about such things going on. I didn’t think more about it, because it was spoken of as the same kind of small scale pilfering from the state which has been widespread in Cuba for quite a while, and goes back to the early 90s, when the island was beset by economic crisis following the collapse of Comecon, the East European Communist trading bloc. It seems that only recently has the illicit beer trade reached the scale now uncovered – 3,000 cartons a week, Rosal told me – which not only casts a dark cloud over the school but threatens its financial stability.

Official Cuban reports about the affair are minimalist. Given the undeveloped state of investigative journalism in Cuba, there are a whole lot of questions which are not only unanswered but not even asked. The most obvious is how this corruption came to be exposed. According to one account, it started with anonymous charges made within the school, which began to circulate beyond its confines, until one of those involved in the trade made the mistake of transferring a cargo between trucks outside the school premises which was seen by a local resident who then called the authorities.

Rosal says that he became aware of a problem soon after he took over the reins at the school two years ago, and he started to try and sort the situation out by sacking someone in the finance office and bringing in his own people, but this may also have been his undoing. Other accounts suggest that Rosal exacerbated the problem, because his appointees were not people vetted by either the Film Institute (ICAIC) or the Ministry of Culture in the normal way—which was only possible because the school has operated with anomalous autonomy. As a senior member of the ICAIC put it to me in another context, no-one in Cuba is fully autonomous. But the film school was a special case: supported by the Ministry of Culture but run by the Foundation for New Latin American Cinema, an international NGO whose President is Gabriel García Marquez (who now suffers from Alzheimer’s and is sadly in no position to run anything), actually no-one was supervising it properly.

At all events, it doesn’t take a lot of wit to realise that there would also be people outside who would have to have been involved. For example, given that obviously far too much beer was being shipped to the school than could have been consumed on the premises, someone at the brewery must have been in on it, and I also learned that at least one person at the brewery, possibly two, have also been arrested. What the affair points to, then, is the network of low or mid-level corruption which such illicit trading creates right across the system, which is partly a consequence of Cuba’s lopsided economy and also contributes to it.

There are other factors, however, which are needed to explain how this happened, including changes introduced in the administrative structure of the school over the years, and lack of oversight by responsible authorities, including the film institute, ICAIC, and the Ministry of Culture itself, as the body responsible for providing the school’s internal running costs. But here one also comes up against Cuba’s dual currency system, since the film school operates, like other institutions, partly with the convertible peso, or CUC, which is pegged to the US dollar, which functions as the currency of the tourist sector and various commodities like beer, and partly in the ordinary peso, or CUP, the currency in which most state workers are paid, which is valued at 25 to the dollar. Apparently everyone at the film school is paid in CUC, so their salaries are much higher than the average Cuban state employee. At the same time, following a bizarre accounting practice, the two currencies are treated as equal for transactions within and between state enterprises. It is said that this helps to control inflation, but evidently does so at the cost of creating cracks which provide opportunities for quotidian corruption. (If you find this explanation confusing, you’re not the only one; I can’t pretend that I really understand it myself.)

Cuba launched a campaign against multifarious forms of corruption soon after Raúl Castro took over as President in 2006, but a new stage was reached only a couple of years ago with the creation of a new national audit office, although it was the provincial audit office which investigated the school once the affair moved beyond anonymous accusations, and the provincial prosecutor who made the arrests. The school was informed on July 1st at an extraordinary meeting of the entire body of staff and students, attended by a bevy of officials including the Minister of Culture, Rafael Bernal. Assurances were given that the Ministry would ensure that the school was able to continue functioning.

The following day, Rosal travelled to Medellin in Colombia where there was a meeting taking place of the council of the Iberamerican Film Authority, from which he returned with a promise of immediate assistance to the school of double the amount already promised. But this was like closing the proverbial stable door too late. Juanjo reports that at the public meeting on 1st July, ‘the Province’s public prosecutor who had just finished a general audit of the school triggered by the beer affair explained in detail many questionable decisions that Rafa had made during his last year as director. Many were decisions that were made without informing, or seeking the proper advice, of other heads of department within the school, including the legal department. For this reason much of the information given by the prosecutor was a surprise for those in attendance at the meeting.’ He adds: ‘Although I’m sure Rafa had the best of intentions for the school, he handled the school’s current situation poorly. The school’s extremely delicate position required visionary direction and ultimately it overwhelmed him. I personally believe the whole situation could have been avoided with the timely intervention of the foundation, however their policy allowed the school full autonomy.’

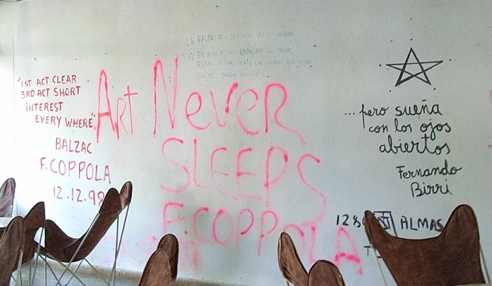

What will happen now? While it seems unlikely that the school is about to shut up shop, it is difficult to see how it can continue the way it has been. For example, the richness of the student experience is partly the result of the large number of filmmakers from different countries who visit the school to deliver specialist workshops each lasting two or three weeks. They include very big names in the world of cinema. The cost to the school of the airfares involved runs to US$0.5m annually. Is this a figure the Ministry of Culture will be happy to stump up? Even the school’s relatively fast internet connection costs upwards of US$135,000 a year. But the EICTV is a unique institution, which has not only helped to form new generations of filmmakers in both Latin America and Cuba itself, but is also the only film school in the world to have received an award from the Cannes film festival, and one fervently hopes that it will get the support it needs and recover to find new life.

LINKS:

En prisión tres trabajadores de la Escuela Internacional de Cine por negocios ilícitos

http://www.diariodecuba.com/cultura/1372978162_4076.html

La Escuela Internacional de Cine y Televisión (EICTV) de San Antonio de los Baños ha comunicado a los estudiantes recién admitidos para el curso regular 2013-2016 que no podrán iniciar sus estudios.

http://www.diariodecuba.com/cultura/1373162203_4117.html

El Estado cubano seguirá respaldando y estimulando a la Escuela

http://www.lajiribilla.cu/articulo/5154/el-estado-cubano-seguira-respaldando-y-estimulando-a-la-escuela-que-fundaron-fidel-y-g

http://www.lajiribilla.cu/articulo/5252/fundacion-del-nuevo-cine-latinoamericano-ratifica-la-larga-vida-de-la-eictv