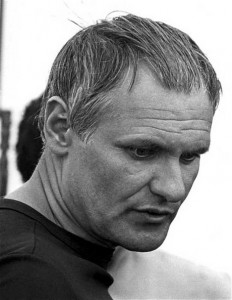

The Round-Up (1965), The Red and the White (1967), The Confrontation (1969), Red Psalm (1972): the films of Miklós Jancsó were one of the most exciting discoveries of radical cinema in Europe in the late 1960s, but hearing of his death last Friday at the age of 92 brings back a personal memory, for at the very beginning of my career as a film maker, I had a brief but hugely positive encounter with him. I interviewed him when he came to London for the opening of The Confrontation in 1969, and me a young film and music critic just then finishing my first short documentary for the BBC. At the end of the interview he inquired what I did ‘because you don’t ask questions like the usual film critic’, so I told him, and he asked if he could see one of my films. I couldn’t show him the BBC film because it was just then in the hands of the editor who was laying the soundtracks, so when he came to the cutting room the next day, I showed him the film I’d made as a student about the filming of Richard Attenborough’s ‘Oh! What a Lovely War’. Unlike the interview, which was conducted through an interpreter, our conversation was limited by my poor French, but what he said was simple enough: ‘I’ve seen lots of films about films, and what I can say is that what I’ve just seen isn’t just a report, it’s a real film!’ You’ll have to take his word for it—the only copy unfortunately got lost—but I owe him a huge debt of gratitude for these simple and very timely words of encouragement.

All the more so because of what he stood for. Obituaries rightly place him alongside Bergman and Antonioni, and speak of the ‘hypnotic beauty and daring technique’ of his films. I would add (staying with European cinema) Fellini, Buñuel, Bertolucci, Resnais and Godard. Each possessed their own distinctive cinematic vision working against the dominant current of ‘the movies’. I am speaking the 60s, of which Régis Debray once wrote that ‘We…learnt, for we were good pupils, that the sirens of ideological error are always singing, on the cinema screen, in novels and in the street, and that few scholars are wise enough to close their ears fully to them. So, to save us from ourselves, we were taught to mistrust our own credulity and our enthusiasms, and to lay in a supply of ear-plugs as a protection.’ [Prison Writings, 1975] We went to the cinema—Hollywood included, of course—to assuage our anxieties in a couple of hours of distraction, but Jancso’s films broke through our mistrust because they taught us a new way of envisaging the problems of ideological error, especially, in his case, in relation to structures of power and authority—themes that exercised us greatly. Instead of the usual narrative language and individualist psychological conventions, the protagonists of Jancso’s films tended to be groups or factions in agonistic relation to power and authority, played out in open or enclosed spaces and choreographed by means of long takes with a constantly mobile camera. His elliptical narrative and balletic long takes—this was obviously not to everyone’s taste, any more than the films of Theo Angelopoulos and Bela Tarr who built on Jancso’s example. But they were allegories on freedom and authority, and this is one of the themes explored in the interview I did with him about The Confrontation, which although set in 1947, was seen as an oblique commentary on the 1968 student riots in Budapest, and hence of pretty direct concern to a 68-er such as myself.

All the more so because of what he stood for. Obituaries rightly place him alongside Bergman and Antonioni, and speak of the ‘hypnotic beauty and daring technique’ of his films. I would add (staying with European cinema) Fellini, Buñuel, Bertolucci, Resnais and Godard. Each possessed their own distinctive cinematic vision working against the dominant current of ‘the movies’. I am speaking the 60s, of which Régis Debray once wrote that ‘We…learnt, for we were good pupils, that the sirens of ideological error are always singing, on the cinema screen, in novels and in the street, and that few scholars are wise enough to close their ears fully to them. So, to save us from ourselves, we were taught to mistrust our own credulity and our enthusiasms, and to lay in a supply of ear-plugs as a protection.’ [Prison Writings, 1975] We went to the cinema—Hollywood included, of course—to assuage our anxieties in a couple of hours of distraction, but Jancso’s films broke through our mistrust because they taught us a new way of envisaging the problems of ideological error, especially, in his case, in relation to structures of power and authority—themes that exercised us greatly. Instead of the usual narrative language and individualist psychological conventions, the protagonists of Jancso’s films tended to be groups or factions in agonistic relation to power and authority, played out in open or enclosed spaces and choreographed by means of long takes with a constantly mobile camera. His elliptical narrative and balletic long takes—this was obviously not to everyone’s taste, any more than the films of Theo Angelopoulos and Bela Tarr who built on Jancso’s example. But they were allegories on freedom and authority, and this is one of the themes explored in the interview I did with him about The Confrontation, which although set in 1947, was seen as an oblique commentary on the 1968 student riots in Budapest, and hence of pretty direct concern to a 68-er such as myself.

There are some good video links here

And here’s a slightly edited version of my 1969 interview:

Remarks on The Confrontation & an Interview with Jancsó