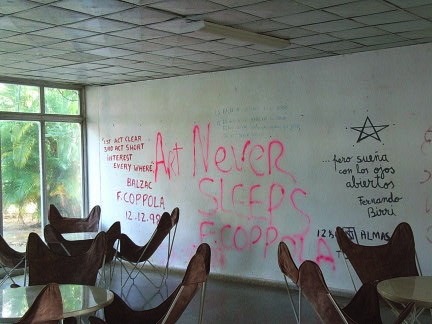

Cuba’s international film school, the EICTV, reminds me of Passport to Pimlico. Set up in 1986, it isn’t actually Cuban, but belongs to the Foundation for New Latin American Cinema (President: Gabriel García Marquez), whose friend Fidel declared it to be ‘not national territory’. If you arrive by the front gates, you have to pass a guard house, but they don’t seem very vigilant, and anyway there’s a back road which isn’t controlled. I’ve been going there every two years or so since the mid-90s to do workshops, much as other people from Britain and in fact all over (although I first went to Cuba in 1979 to write a book on Cuban cinema, and then filmed there on several occasions in the 80s for Channel Four). There’s a permanent staff, but also lots of visitors. On this visit there were workshops being given by film-makers from Chile, Peru, Argentina, Germany and Spain, and the foyer has graffiti scrawled on the walls by Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, Costa Gavras, Ettore Scola and Stephen Friers among others. Distinguished company indeed!

Returning to Cuba almost two and a half years after my last visit, the greatest pleasure lies in renewing old friendships. Of course I’m eager to know how people feel about Fidel’s illness and its effects on the way the country feels about itself. One friend – an intellectual and Party member – answers with a very suggestive metaphor. The captain of Airplane Cuba is old, ill and tired, and has handed control over to his co-pilot, who is struggling to keep the aircraft on course because it’s flying through a seemingly endless storm. Behind him the navigator is trying to maintain contact with ground control. The biggest problem is that fuel is running low, and everyone knows they have to change course, otherwise they’ll have to make an emergency landing.

Meanwhile the cabin crew have the job of keeping the passengers happy amid the turbulence. There’s quite a lot of grumbling but they’re mostly pretty well behaved. But even the old and faithful have become somewhat sceptical about the destination, although no-one has a clear idea of where they should now be heading. Another friend tells me about a comrade, a Party member. She hopes, of course, that the captain will recover his health and enjoy many more years of life, but if he takes back the controls, she says, she would leave the country. Perhaps this is just a rhetorical flourish, because this is a drastic step which isn’t so easy to undertake, but in fact, following a recent statement by the foreign minister Felipe Perez Roque, there is also an expectation that controls on foreign travel are soon to be eased.

Many of the passengers belong the generation which was born around the time the aircraft took off. They did not experience the previous regime but they know from their parents and grandparents what it was like. For them, the problem is that the crew has been flying blind for more than fifteen years – ever since the other aircraft belonging to Airline Socialism switched allegiance to another operator. As for the youth, they are eager to communicate with their cousins who left on a different flight for a different destination, and they’re frustrated because these cousins of theirs have sent them mobile telephones which don’t always work properly. But nor do the smoke detectors in the toilets, and one or two of them decide to have a smoke. When the stewards threaten them for breaking the law, the other passengers intervene, and tell the crew to stop hassling them.

There are several musicians on board. Some of them have a penchant for songs with lyrics that are somewhat risqué. For example, Frank Delgado sings about what goes on when power cuts happen and the lights go out (although on this visit I didn’t here any complaints about them), or about an old man trying to make ends meet by selling his books, but no-one wants to buy them because the authors, with names like Marx and Engels, are passé. The official record label hasn’t offered him a recording contract, so he records his albums in countries like Mexico and Argentina. Nevertheless he is extremely popular, especially among the young intelligentsia and the students, who attend his peña (club) and flock to his public concerts, which are always packed out. The first time I went to one of these, a few years ago, I was struck by the fact that the audience evidently knew the songs backwards and were singing along with him. I went back to the film school and asked one of the students if he knew where I could get hold of one of his records. No problem, he said, I’ve got them all on my computer. When I met Delgado and asked him about this, he had no complaints. On the contrary, he said, he didn’t care about the money he wasn’t getting, because it demonstrated his popularity and built up his audiences.

Digital technology has begun to subvert the vertical control of the country’s media, and this has contributed to a significant shift which has occurred in ideological position taking. The State retains strict control over the public media, but there is now a parallel sphere which operates through both the circulation of digital media and by means of email. A little over a year ago, television broadcast a series of interviews with forgotten figures from the early 70s, including Luis Pavón, who was in charge of the National Council for Culture during the period which later came to be known as the ‘quinquenio gris’, the five grey years (or according to some people, black), without even mentioning the Council. Almost immediately emails began to circulate among artists and intellectuals criticising the producers. At one point the circulation list reached some 1500 names, a public debate was held under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture (with hundreds more people turning up than the hall was capable of accommodating, even after the venue had been moved), and in the end the television station was forced to admit that the programmes had been a mistake. As the political scientist Rafael Hernández, editor of the polemical journal Temas, points out to me, that people felt free to participate in this electronic debate, knowing full well that it was being monitored by the authorities, was a clear indication that the balance of ideological forces had already shifted definitively away from the hard liners, the communist fundamentalists nowadays known, with typical Cuban humour, as the Talibans. In fact he dates the beginning of the ‘apertura’ or opening to the mid-1990s, when Temas was founded, with a brief from the Party Central Committee to engage in debate.

Internet connectivity has been available since the renovation of telephone system by a Mexican company a good many years ago, and email is available not only at people’s places of work but also on home telephone lines, although the latter is provided without access to the web. While web access at work places is heavily filtered, I know several people – academics and other professionals – whose access is unrestricted. Hernández points out that despite these restrictions, the effect is extensive, especially since many people have family and friends abroad who can (and do) easily send attachments. One result is that people no longer bother about the propaganda beamed into Cuba by radio and television stations from the USA. But the effects of digital technology on the circulation of information within Cuba are considerable, precisely because messages received can easily be circulated further, and Cuba, as someone put it to me back in the 80s, is the country of ‘chiste y chisme’ – jokes and rumours; in other words, where information travels quickly by word of mouth. (An example of the former, which illustrates changing attitudes to Fidel: One day, Fidel instructs Pepito to come up with a plan to solve the housing problem in Havana caused by immigration from Oriente province, where Fidel himself hails from. A couple of days later Pepito comes back and says, ‘OK, we need 400 buses and a Mercedes Benz.’ ‘But why the Mercedes Benz?’ asks Fidel, and Pepito replies, ‘Well, do you want to travel in one of the buses with everyone else?’)

But digital technology is not only about the internet, as the circulation of music demonstrates, and it has also succoured a lively sector of independent video production. One of the players on the scene is of course the EICTV, whose students, coming from other Latin American countries and going out onto the streets to film short documentaries, began to tackle subjects which were novel and challenging. Another player is the Asociación Hermanos Saíz, a cultural association for youth activities with some 3,500 members across the country and all the arts. Affiliated to the official writers and artists association, UNEAC, it runs a film and video workshop which is sponsored by the ICAIC, Cuba’s state film institute, and the producer of the films by directors like T.G.Alea, Humberto Solás, Santiago Alvarez and many others, whose work established Cuban cinema as one of the liveliest young cinemas in the world in the 1960s. The institute now holds an festival of young directors. Then there are two NGOs, the Movimiento de Video, mainly devoted to amateur video and dating back to 1988, and the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba, funded by a pair of German art collectors, Peter and Irene Ludwig, and angled towards video art.

For the last ten years or so, television has played an unintended role which has solved the big problem for the independent videographer of how to make a living and finance themselves. It started about ten years ago when ICRT, the state television company, found itself short of content and because of the country’s economic crisis, lacking production resources, just as new desktop video began to be taken up by a new generation of film-makers who were often graduates of one of the country’s two film schools.

It works like this. A client, who might be a musical group, a theatre company, a government department, or a magazine like Temas, wants some publicity, or has a campaign to run, or would like to disseminate its activities. If they went directly to television, the response would be, very interesting but we don’t have the resources. So someone came up with the idea of offering them ready made material, and the television people said, OK, we’ll have a look. The result is now a regular supply of items ranging from 30 second spots to the short programmes which Cubans call ‘videoclips’. Television is happy because they get free content. The clients are happy because they get wider publicity at a very reasonable cost. The videographers are happy because they’re able to make a modest living and just about finance their own work. Of course, items made for television have to conform to the requirements of the broadcast media, but this is not true of independent production not made for television.

If the diffusion of video films, like the debate about the ‘quinquenio gris’, suggest that the ideological opening is genuine, the impression is confirmed a little ambiguously by shifts of political balance inside the Party. The Central Committee has three offices to look after ideological areas, one responsible for ideology properly speaking, one for science, and one for culture. Back before the 90s, the man in charge, one Carlos Aldana, was a member of the Party Central Committee and a hard-liner who tried to block the critical goings-on at the film institute. The new office chief isn’t, although he’s not known for any liberal streaks. But the present Minister of Culture, Abel Prieto, is a career politician rather than a career bureaucrat, an erstwhile writer, university teacher, director of the prestigious publishing house Letras Cubanas and president of the UNEAC. At 57 a comparative youngster among the governing Buro Politico, he is also a popular figure, who cultivates a noticeably off-beat image.

None of this implies in any way that Cuba is about to recant the principles of revolutionary socialism. Another writer friend of mine says that the situation is really very simple – the government is not about to give up power, and then he corrects himself: ‘I mean, the Party.’ To underline the point, you can make a video, he says, about anything (other than pornography) except for one thing: you cannot advocate the formation of another political party. Nevertheless, it very much looks as if significant changes are on the cards, and pretty soon, because, as Hernández puts it, what is now at stake is the very credibility of the government.